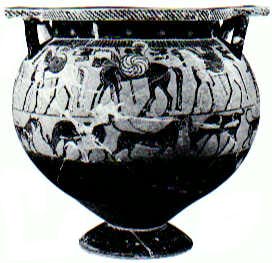

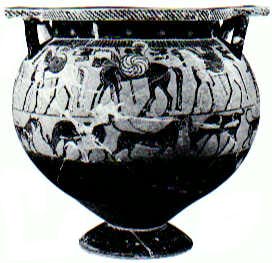

Black-figured Corinthian krater, c. 560 BC.

Etruscan

Museum, the Vatican. |

Guide to Reading the Iliad

The Iliad is an epic poem, composed around 800-725 B.C. and written

down sometime between 725 and 675 B.C. The ancient Greek word epos,

from which our word "epic" comes, means "word, utterance, poetic utterance,"

and the Iliad is precisely that. While we tend to think of a poem

as a short composition in verse about personal feelings, an epic is quite

different. Epic poetry is narrative, usually telling the story of a great

culture hero and his exploits. (The Iliad tells the story of Achilles,

and how his anger affected the fighting in the great war of Troy.) There

are two types of epics, literary and folk. Folk epics are composed anonymously

or traditionally, and attributed to shadowy ancient authors (like Homer),

while literary epics are written by one person (like Virgil). Folk epics

originate in oral cultures (those without writing), while literary epics

come from literate cultures.

The Heroic World

Iliad: Reading Assignments, Summaries, Notes,

and Questions

Other LINKS |

Oral composition

Both the Iliad and the Odyssey originated in the oral

tradition, in which a poet or singer, accompanying himself on the lyre

or harp, sings traditional tales of heroes. While the essential plot elements

of a traditional story cannot be altered, a gifted poet can shape the material

in complicated and interesting ways. For example, in the Iliad,

Homer centers his tale around the consequences of the quarrel between Agamemnon

and Achilles. The poet chooses not to tell other well-known episodes of

the war at Troy (for example, how the war started and how it ended) because

he wishes to concentrate on the issues of death, anger, and honor raised

by the quarrel. In fact, the Iliad and the Odyssey exhibit

such complexity and ingenuity of structure and theme that I believe they

were both put together out of traditional materials by a single poet.

Rather than memorizing the whole song, the oral poet composes it as

he sings, stitching the poem together from a vast repertoire of memorized

phrases (called formulas) which fit the meter (called dactylic

hexameter) of the song. The Greek verb for such a singing-performance

is rhapsoideo, "I rhapsodize, stitch song together." Thus, the oral

poet needs to remember two things: 1) the essential story, and 2) many

formulas (examples: "strong-greaved Achaeans" or "long-haired Achaeans").

Originally for this kind of poetry, "Singing, performing, composing are

all facets of the same act" (Lord 13). (Bernard Knox gives some more examples

of formulas and discusses scenarios for how oral poetry gets written down

on pp. 15-22 of the introduction to the Iliad.) As he sings, the

poet is guided by his years of practice and by his knowledge of the story.

A story-line, heroic type-figures, the song, the meter, and the formulas

all help to keep the material memorable.

Because these poems were composed orally, they exhibit unique characteristics.

You should be alert to these features as you read. With so many formulas,

some parts of the poem will repeat. For an oral poet, however, such repetition

is not a fault, but a vital technique (Lord 3Ė67). Repetition is a psychological

necessity in oral discourse, which vanishes as soon as it is uttered: "the

mind must move ahead more slowly, keeping close to the focus of attention

much of what has already been dealt with. Redundancy . . . keeps both speaker

and hearer surely on the track" (Ong 39-40). Sometimes a whole series of

lines will repeat, not because the poet is bored or uninventive, but because

oral poets often describe similar situations in the same formulaic manner.

Also, the poet could cruise through these repetitive passages while thinking

of what was coming up next in the poem.

Repetition is not only a psychological necessity, it also keeps the

meter and the memory flowing smoothly. For example, formulas will often

repeat for metrical reasons: "Odysseus is polymetis (clever) not

just because he is this kind of character but also because without the

epithet polymetis he could not be readily worked into the meter"

(Ong 58-59). The word polymetis (also translated as "versatile"

or "resourceful") is a special kind of formula called an epithet,

an adjective or adjectival phrase which describes, in appropriate metrical

form, characteristics of gods or heroes. Examples: "versatile Odysseus"

or "Zeus the cloud gatherer." Often, an epithet will substitute for a character's

name, as when, for example, Agamemnon is called "son of Atreus" or "Atrides."

(The Greek suffix "-ides" means "son of.") The translator of our edition

of the Iliad, Stanley Lombardo, tries to a) limit the number of

epithets, and b) vary their wording, so you may not notice these epithets

in his translation as much as you might in others.

Since an oral society possessed no written archives, lists, or books

and had no libraries, computers, or videotape on which to store information,

important cultural or historical knowledge was encoded into the more easily

remembered form of a story. The Iliad contains a long catalogue

or list of men and ships (115-127). Notice how this catalogue is narrated

as a series of actions, which are more memorable than a mere list would

be. And since the oral poem was the repository of the entire cultural memory

of a people, it also contains digressions, or breaks in the main

story-line which describe the history of various props (such as a scepter

or a weapon) or which relate the ancestry of a warrior in what might seem

to us to be over-elaborate detail. However, these details were prized by

the original audience, some of whom might trace their ancestry back to

characters in the story. Digressions also gave the audience the sense of

a full and living cultural background to the story.

Because poets' powers of memory were considered godlike, the ancients

spoke of their songs as being inspired by nine goddesses called the Muses.

The Muses were the daughters of Mnemosyne ("memory") and Zeus. By claiming

that the Muses inspire their songs and know everything ("you are everywhere,

you know all things--") while poets know nothing ("all we hear is the distant

ring of glory, we know nothing" [Iliad 2.575-576]), poets authenticated

their individual utterance as the communal wisdom of gods and men. One

scholar goes so far as to say that the "formulas are the . . . words spoken

by the Muses themselves: they are recordings of the Muses who were always

present when anything happened" (Nagy 272).

Two other techniques of oral poetry are designed to make the poem immediate

and exciting for listeners. Having no wide screens, special effects, or

dolby soundtracks, the ancient poets relied on "winged words" to keep their

stories vivid. For example, epic similes, or extended comparisons,

help the audience visualize and feel scenes, actions, and emotions. These

similes are usually precise and quite moving. Oral poets also performed

the speeches of the characters as a modern-day actors might. Such

emotional inflections and tones of voice are difficult to create on the

printed page; we will try to re-create the oral moment by listening to

sections of a tape of the Iliad in class. When recited, oral poem

are events, performances, and reaction to oral poems is communal and physical

rather than solitary and silent. Since they are close to the lifeworld

and not neutral signs on a white page, oral poems stress verbal and physical

struggle over reflective thought and exterior action over interior psychology.

The other side of verbal name-calling is the "fulsome expression of praise"

(Ong 45). Thus, the speeches of characters in the Iliad are often

either boastful or disdainful, full of extravagant praise or blame.

Though literate cultures often look down upon those who cannot read

or write, Walter Ong reminds us that oral expression "can be quite sophisticated

and in its own way reflective. Navaho [storytellers] can provide elaborate

explanations of the various implications of the stories . . . and are perfectly

aware of such things as physical inconsistencies (for example, coyotes

with amber balls for eyes) and the need to interpret elements in the stories

symbolically. To assume that oral peoples are essentially unintelligent,

that their mental processes are 'crude', is the kind of thinking that for

centuries brought scholars to assume falsely that because the Homeric poems

are so skillful, they must be basically written compositions" (57).

Nor should we assume, Ong continues, that oral thought is somehow "prelogical"

or "illogical" in any simplistic sense. Oral folk "understand very well

that if you push hard on a mobile object, the push causes it to move. What

is true is that they cannot organize elaborate concatenations of causes

in the analytic kind of linear sequences that can only be set up with the

help of texts. The lengthy sequences they produce, such as genealogies,

are not analytic but aggregative. But oral cultures can produce amazingly

complex and intelligent and beautiful organizations of thought and experience"

(57).

Words are thought to have an almost magical power in oral cultures because

they are events, not signs. Ong writes: "Without writing, words as such

have no visual presence, even when the objects they represent are visual.

They are sounds. You might 'call' them back--'recall' them. But there is

no where to 'look' for them. . . . They are occurrences, events" (31).

The Hebrew term dabar means both "word" and "event." In contrast,

written words on the page are inert, just objects. Ong notes that the standard

Homeric epithet "winged words" conveys a sense of "evanescence, power,

and freedom" (77).

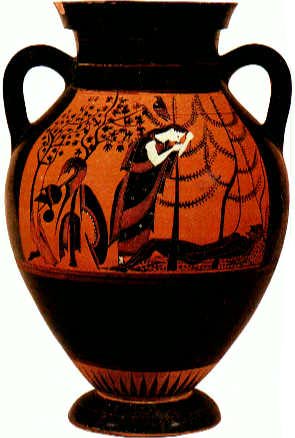

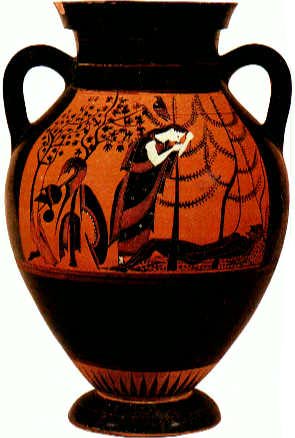

Eos (goddess of dawn) mourns her dead son,

the warrior Memnon. Attic black-figure vase,

c. 530 BC. Etruscan

Museum, the Vatican.

Here's a

different version of the same scene. |

The Heroic World

The Iliad narrates the consequences of the anger or rage of Achilles.

The Greek word menin ("wrath" or "rage") is the first word in the

epic. Because of his anger, Achilles withdraws from the war and causes

his comrades the Achaeans to suffer "countless losses" (1.2) or deaths.

Death is central to the poem. Seth Schein writes:

The overwhelming fact of life for the heroes of the Iliad is

their mortality, which stands in contrast to the immortality of the gods.

We see the central hero of the poem, Achilles, move toward disillusionment

and death to reach a new clarity about human existence in the wider context

of the eventual destruction of Troy and in an environment consisting almost

entirely of war and death. This environment offers scope for various kinds

and degrees of heroic achievement, but only at the cost of self-destruction

and the destruction of others, who live in the same environment and share

the same values. (1-2)

As we will see when Odysseus visits the underworld in the Odyssey,

the afterlife in Homer is a dull, shadowy, listless affair, in which empty

and witless souls wander, shells of their former selves. Therefore, it

is important that the hero achieve some meaning on earth by the way he

conducts his life and achieves his inevitable death. Life becomes meaningful

and valuable for the hero because he can win honor (in Greek, timé)--the

"public esteem" (Dodds 17) of his fellow-warriors in this life and glory

(in Greek, kleos)--the "reputation" (Schein 71) which poets will

sing of after his death. |

In book 12 of the Iliad, the Lycian hero Sarpedon begins a pep-talk

to his friend Glaucus with a rhetorical question:

Glaucus, you know how you and I

Have the best of everything in Lycia--

Seats, cuts of meat, full cups, everybody

Looking at us as if we were gods? (12.320-324)

Sarpedon then proceeds to tell why they are honored with "the best of everything:"

Well, now, we have to take our stand at the front,

Where all the best* fight, and face the heat of battle, *aristoi

So that many an armored Lycian will say,

'So they're not inglorious after all,

Our Lycian lords who eat fat sheep

And drink the sweetest wine. No,

They're strong, and fight with our best.' (12.326-332)

Notice that the visible marks of honor are gifts, expressed here as the

best cuts of meat. The Greek word for honor, timé, can also

mean "price" or "value" (Schein 71). Those who are the best fighters should

receive the largest share or portion of the spoils of war. The more gifts,

the more stuff a hero accumulates, the more honor he has. Somewhat paradoxically,

one can also gain honor by being big and liberal and noble enough to give

gifts to others. Notice also that Sarpedon implies that ordinary fighting

men honor their leaders at least in part because these leaders protect

them. When Achilles withdraws from the war, he allows his own personal

sense of injured honor to outweigh his duty to protect the rest of his

less-gifted, less-honored comrades. In contrast to honor, glory

occurs mostly after death, when poets can sing of a hero's immortal deeds.

In the world of the Iliad, the honors and gifts showered upon a

hero come to an end with death, but his glory lives on forever in the stories

that poets sing. By achieving imperishable glory, a hero ensures that his

name and fame will live on after he has gone on to the rather meaningless

afterlife in the underworld.

The opposite of glory (kleos) is shame or disgrace (aischros).

Glorious actions were praised, while shameful actions were blamed. A shameful

act was not necessarily considered immoral or wrong, but "ugly" (the other

meaning of aischros). [In this sense, the opposite of shame (aischros)

is not glory (kleos), but "beauty" (kalos).] The heroes'

code of honor stressed achievement of an exterior amoral ideal rather than

an interior moral good. When heroes commit disgraceful acts, they do not

feel guilt, the inner consciousness of moral wrong, but shame,

the loss of face that comes from looking ugly in front of public opinion

(Dodds 26). One reason Achilles seems selfish to us is that he is operating

in a shame culture, while we are very much a part of a guilt culture. The

above considerations on honor, glory, and shame should help you interpret

the quarrel in book 1 and Achilles' refusal to re-enter the war in book

9 of the Iliad.

The Iliad explores the limits and contradictions of the honor-glory

system of meaning. One limit--death--is omnipresent. As Seth Schein points

out, one of the tragic aspects of this system is that the hero can win

honor and glory only through the death and destruction of others (71-72;

82-84). The deaths of humans are in some sense fated to happen. One of

the chief Greek words for fate, moira, means "portion" or

"a part or division." It can mean one's portion of a meal, of the spoils,

one's inheritance, or one's portion in life, or what one is due. Sometimes

the word used for the portion which a hero receives when he is honored

is the same as this word for fate--moira (Nagy 134-135). Agamemnon

dishonors

Achilles by taking away part of his just portion, namely Briseis. But fate

can be seen as more than one's "portion" or "lot" in life: the word can

also be used to speak of death, of the will of Zeus, of one's station in

the hierarchy (it is Hephaistos' fate to be a lame blacksmith for the gods),

of "how things turn out," and even of one's abilities, both excellent and

pathetic. Another limit to the system of honor and glory is human weakness.

When a hero boasts that he can achieve impossible feats, when he neglects

to honor the gods, when he goes beyond established human customs, or when

he attempts feats that only a god could accomplish, he is guilty of arrogance

and pride (in Greek, hubris)--or "outrage" (Nagy 152). Great

heroes often run the risk of hubris since they are godlike and tend

to go beyond human limits.

Great heroes tend to exhibit certain excellent qualities and certain

weaknesses. For example, Odysseus' excellence is his clever, scheming mind,

while Achilles' excellence is his sheer force and power in battle. The

Greeks called a person's particular excellence his or her aretê,

which has also been translated as "virtue." The Greeks thought that each

person should "develop his aretê, or inborn capacities, so

far as he possibly can" (Bowra 211). Often, a hero's excellent qualities

betray a weak side. For example, Achilles' fiery fighting spirit is related

to his equally fiery temper. Other interesting words are cognate with aretê

(excellence). For example, a hero's great, glorious feats are called his

aristeia--literally,

his "best work." And the aristocrats were the aristoi, or

the "best" people.

But how do women fit into this heroic world? Can they be heroes? Can

women win honor and glory? Because they cannot fight, women cannot exactly

be heroes, but they may win honor and glory in their own spheres of excellence,

or aretê. Thus, women can win glory and fame by their excellent

weaving or child-rearing. However, the womenís sexual behavior is much

more subject to praise or blame than the menís. In the Odyssey,

for example, Penelope is famous for being faithful to Odysseus, while in

the Iliad Helen is notorious for being unfaithful to Menelaus. Looked

at another way, Menelaus was dishonored by having a prized possession--his

wife Helen--stolen away from him by Paris. Away from the battles for glory,

women had considerable influence over the management of the oikos--an

extended noble family. The agricultural (grain, olives, wine) and "industrial"

(cloth, craftwork) products of such large households (Priam has 50 sons)

formed the basis of the ancient economy. In fact, the Greek word oikos

forms the root of our English words "economics" and "ecology." Visitors

to such large and rich noble households could expect gracious and unfailing

hospitality (xenia). By honoring his "guest-friend" (xenios)

with expensive gifts, a nobleman could display how much wealth and honor

(the two were virtually synonymous) he had obtained. In book 6 of the Iliad,

Diomedes and Glaucus agree not to fight one another because their ancestors

had once entered into a guest-friend relationship.

The Greek system of hospitality, gift-giving, and guest-friendship was

not

supposed to be an open invitation to freeloaders, however. In actuality,

it was a system of exchange. In his Works and Days, Hesiod explains

how the system should work:

Return a friend's friendship and a visitor's visit.

Give gifts to the giver, give none to the non-giver.

The giver gets gifts, the non-giver gets naught.

And Give's a good girl, but Gimme's a goblin.

The man who gives willingly, even if it costs him,

Takes joy in his giving and is glad in his heart.

But let a man turn greedy and grab for himself

Even something small, it'll freeze his heart stiff. (34; lines 399-406)

When several extended households in the same neighborhood united together

under the leadership of a king, the resulting society was called a polis--the

Greek word for "city-state." Some Greek poleis later developed into

democracies ruled by the voters--male citizens with property. (For some

background, see Murnaghan's introduction, pp. lii-liv.) The polis

is under the protection of its best warriors, who win glory and honor by

killing the warriors from other poleis, destroying their cities,

carrying off booty, and enslaving women. (Later, the many poleis

developed armies made up of citizen-soldiers called hoplites.) The

warlike pursuit of honor and glory might seem to contradict the civilized

institution of guest-friendship (hospitality), and at its extremes, it

does. Women, who cannot win glory by killing, sometimes point out the terrible

human costs of this heroic system. (See Andromache in book 6 of the Iliad).

Taken to its extreme, the heroic, manly pursuit of honor and glory leads

to the destruction of civilized life--the obliteration of the polis

of Troy. (In the Odyssey and the Theogony, however, the heroic

exploits of Odysseus and Zeus are seen as necessary for re-establishing

order to the polis and the universe respectively.) In class, we'll discuss

what, if anything, we think Achilles has learned about the high price of

honor by the end of the Iliad. We'll also try to figure out what

Homer thinks about the contradictions between the glory (death and honor)

and civilization (oikos and polis) that he presents so well

in the Iliad.

Works Cited

-

Bowra, C. M. The Greek Experience. New York: NAL, 1964.

-

Dodds, E. R. The Greeks and the Irrational. Berkeley: U of California

P, 1951.

-

Hesiod. Works and Days and Theogony. Trans. Stanley Lombardo.

Indianapolis: Hackett, 1993.

-

Homer. The Iliad. Trans. Stanley Lombardo. Introduction Sheila Murnaghan.

Indianapolis: Hacket, 1997.

-

Lord, Albert. The Singer of Tales. New York: Atheneum, 1970.

-

Nagy, Gregory. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic

Greek Poetry. New York: Viking, 1979.

-

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word.

London and New York: Methuen, 1982.

-

Schein, Seth. The Mortal Hero: An Introduction to Homer's Iliad.

Berkeley: U of California P, 1984.

LINKS

Back to:

CLA201 home page / links

CLA 201 Syllabus