Notes on the Writings of E. E. Cummings

by Michael

Webster

These notes are limited to elucidating allusions and / or quotations which

might puzzle that elusive and very un-Cummings-like

personage, the "general reader."

I have tried—not always successfully—to

avoid the temptation to interpret the poems.

I have not annotated allusions that most literate

readers should know, nor have I deciphered all

of Cummings' dialect spellings. For some suggestions

on interpreting Cummings' visual and syntactic

deformations, see "Deciphering

Cummings."

To find notes to specific poems, click on book titles below, or scroll

down to individual first-line"titles" of poems, highlighted in green. Notes

to the poems begin with the page number in Complete Poems (Liveright,

1994). [Page numbers to the new "revised,

corrected, and expanded" edition of Cummings’ Complete

Poems (Liveright 2016) will be added after

the first line (or "title") with the designation "CP2."]

|

Tulips & Chimneys (1922 Manuscript)

The 1994 Complete Poems publishes

Cummings' original 1922 manuscript of Tulips

& Chimneys

as established by Cummings'

editor, George James Firmage. When first

published in 1923, Tulips and Chimneys

contained only 67 of the 104 poems in the 1922 manuscript.

As Richard S. Kennedy wrote: "For

Tulips and Chimneys,

Thomas Seltzer had gingerly avoided the most experimental

of the poems and passed over those

whose subject matter might startle readers

who were still shocked by a writer like Theodore

Dreiser" (Dreams 252). Later,

"Lincoln Mac Veagh of the Dial Press looked over

the remaining poems and selected forty-one

for a published volume" (Kennedy, Dreams 252). This

book, titled XLI Poems,

was published in 1925. Cummings gathered the

remaining "most startling"

poems from the original manuscript, adding

to them some poems he had written recently.

This group of poems was privately printed, also

in 1925, to avoid censorship. These last

naughty leftovers and their new cousins Cummings entitled

& [AND], using "the ampersand which

Seltzer had denied him in Tulips

and Chimneys" (Kennedy,

Dreams 252-253).

3-7. "Epithalamion" [Thou

aged unreluctant earth who dost"] (CP2: 3-7)

This poem was commissioned by

Cummings' friend, mentor, and patron,

Scofield Thayer, to celebrate Thayer's

marriage to Elaine Orr, June 21, 1916. Thayer paid Cummings the "extraordinary

sum" of $1000 for the poem.

(See Kennedy, Dreams 111-113.) Alison

Rosenblitt discusses the classical heritage

of this poem in her E. E. Cummings' Modernism

and the Classics (136-137).

(3) the god . . . whose

cloven feet = Pan, licentious woodland

deity. A dryad is a wood nymph.

(3) that delicious boy

= Adonis. one goddess = Aphrodite

(Venus).

Chryselephantine Zeus

= statue of Zeus

at Olympia, “a giant seated figure, about 13 m (43

ft) tall, made by the Greek sculptor Phidias

around 435 BC.” The statue is called

"chryselephantine" because was made

of gold (chrysós) and ivory (elephántinos)

panels molded over "a wooden substructure."

Cummings may also be making a private reference

to his own totem animal, the elephant.

(3) Nike = smaller

sculpture of the winged goddess of Victory

held in Zeus' right palm.

(3) diadumenos =

"diadem-bearer" [Greek],

a figural type of the sculptor Polykleitos

(5th century BC) depicting "the winner of an athletic

contest at a games, still nude after the contest

and lifting his arms to knot the diadem, a ribbon-band

that identifies the winner."

(4) victorious Pantarkes

= local hero Pantarkes of Elis, who

"won the boy's wrestling at Olympia in 436 BC," and

who was a favorite of the sculptor Phidias

and reportedly the model

for the sculpture of "a triumphant athlete that

stood at the base of the statue." Ancient sources

also claim that Phidias carved the words "Kalos

Pantarkes" ("Pantarkes is beautiful") on Zeus'

little finger.

(4) how fought the looser

of the warlike zone = Heracles, whose

ninth labor required him to obtain the magic

girdle (“zone,” or sash) of Hippolyta,

queen of Amazons. Hippolyta was the

only Amazon to marry: she was the first wife

of the hero Theseus, and, as the next line says, mother

of “tall Hippolytus.”

|

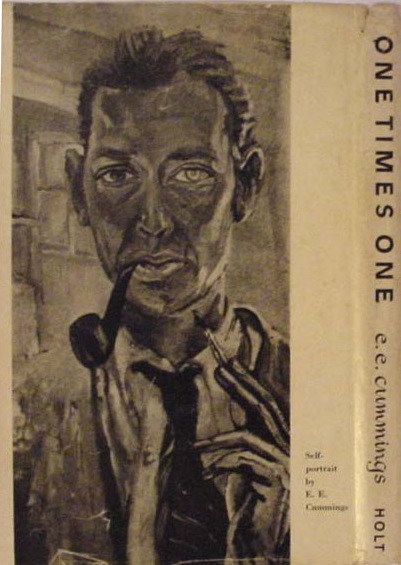

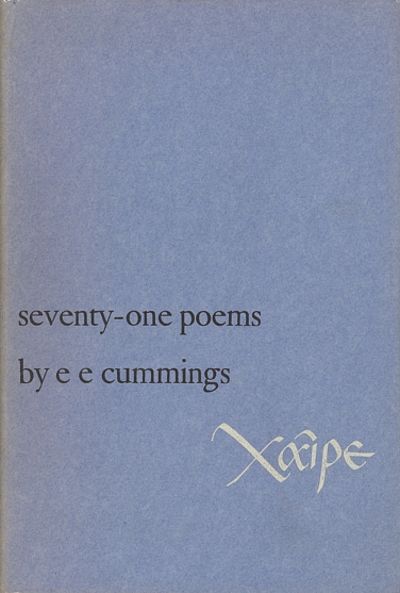

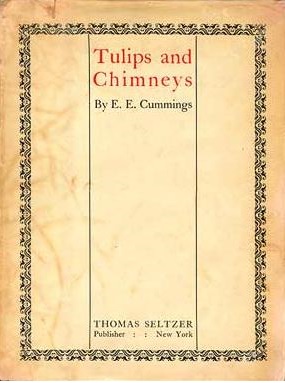

Dust jacket cover of Seltzer's truncated

first edition of Tulips and Chimneys

(1923)

|

3-7. "Epithalamion" [continued]

(4) Selene = goddess

of the moon, sister of the sun god Helios.

Selene's car = her chariot. We see

depicted on the pedestal of the statue of Zeus

the moon sinking in the ocean while the sun rises

faintly in the east.

(4) Danae

= mother of the Greek hero Perseus

and daughter of King Acrisius of Argos. She

was impregnated by Zeus, who visited her in the form of a

shower of gold.

(6) athanor = furnace

used in alchemy.

(6) goddess = Aphrodite,

whose crippled thunder-forging groom

is the blacksmith god Hephaistos.

the loud lord of skipping maenads

= the wine god Dionysos.

Discordia's apple refers

to Eris, goddess of Strife, who arrived

uninvited at the wedding of Peleus and Thetis, and

offered a golden apple to the fairest goddess. "Three

goddesses claimed the apple: Hera, Athena and

Aphrodite. They asked Zeus to judge which of them was fairest,

and eventually he, reluctant to favor any claim himself,

declared that Paris, a Trojan mortal, would judge their

cases." At the famous scene known as The

Judgement of Paris, Aphrodite bribed Paris by offering

him the most beautiful woman in the world, Helen. Of course,

Paris chose Aphrodite as the winner of the beauty

contest, thus setting into motion the events that led to

the Trojan War. the sacred shepherd = Paris.

(7) the tall boy god of everlasting

war = Ares, god of war, who had an

affair with Cytherea, or Aphrodite.

8."Of Nicolette" ["dreaming in marble all the castle

lay"] (CP2: 8)

Richard S. Kennedy notes that

this poem is a "free translation of the sequence

in Aucassin et Nicolette in

which Nicolette

descends from her prison tower." Kennedy

further comments that the "obvious model for the

style is [Keats'] 'The Eve of St. Agnes' " (Dreams 76). Cummings' poem romanticizes the prose

description of the escape in the medieval

French chantefable, which mentions (in Andrew

Lang's translation) Nicolette's bruised and bleeding hands,

her difficulties in climbing

out of the moat, and her fear of "wild beasts,

and beasts serpentine" (31-32).

9-19. SONGS (CP2: 9-20)

For an analysis of these nine

poems as "songs of death," see J. Alison

Rosenblitt's E. E. Cummings' Modernism

and the Classics (137-165).

15. "All in green went my love riding"

(CP2: 15)

First published in The Harvard

Monthly [62.1 (March 1916): 8-9] with

the title "Ballad." On April 5, 1916, the founder

and editor of Poetry Magazine, Harriet Monroe,

visited the New England Poetry Club. Also invited

was the recently founded Harvard Poetry Society, whose

members included S. Foster Damon, John Dos Passos, and

E. E. Cummings, then in the last semester of his MA year

at Harvard. In her account of the visit, Monroe says that

though she couldn't remember the names of any of the students

who attended, she vividly recalled several of the poems that

they read at the meeting, among them "a ballad of really

distinguished quality, showing a feeling for recurrent tragic

rhythms, and a delicate use of a varied refrain" ("Down East" 89). This description sounds very

much like "All in green went my love riding," and since

Cummings had published the poem just the month before

in the Harvard Monthly, it is very likely that he

read it at the meeting. Monroe concludes her account by writing

that she "could scarcely overpraise the work of these students,

or the enthusiasm which has carried them so far in the one short

year since their club was founded" (89).

Will C. Jumper argues that the persona (speaker) of the poem is a woman.

Other scholars (William Davis, Cora Robey,

Barry Sanders) see the speaker as male and

the rider as female. In addition, they debate to what

degree the rider in the poem may be equated with the goddess

Artemis / Diana. Thomas R. Frosch asserts that "the critical

debate about the gender of the speaker and 'my love' is unresolvable,"

while noting further that "the uncertainty of gender in

the poem" extends to the deer, first described as " 'Four red

roebuck,' then becoming 'Four fleet does,' and then becoming

'Four tall stags' " (67). In her blog post "E. E. Cummings'

'All in green went my love riding'," Alison Rosenblitt

notes that in early drafts of the poem, "the rider is

unambiguously male."

Forth went my lord to hunt

Into the dawn my lord rode,

In green

And a merry deer ran before

Nevertheless, she concludes that "the poem as we have it, at least if considered

outside of the 'Songs' context, is ambiguous as to the gender of speaker

and beloved." Likewise, in her book E. E. Cummings' Modernism and the

Classics, Rosenblitt sees the poem's "evocation" of Diana as

deliberately "ambiguous" (155). She further notes in her blog post that this

"rare exploration of gender ambiguity in Cummings coincides with a Swinburnian

moment in his poetry." Both blog and book rather convincingly detail what

Rosenblitt sees as verbal echoes in the poem of Swinburne's "Itylus" (Modernism 154). See also Gary

Lane, I Am (59-63).

Links:

16.

"Where's Madge then," (CP2: 17)

This poem echoes François Villon's "Ballade des dames du temps

jadis" (1462), which asks: "Tell me where, in

what country / Is Flora the beautiful Roman / Archiapiada

or Thaïs" (Villon 47; trans. Galway Kinnell).

17. "Doll’s boy ’s asleep"

(CP2: 18)

According to Richard S. Kennedy, this poem was composed

in the fall of 1917, while Cummings was in detention

in the Enormous Room at La Ferté

Macé (Dreams 152). Alison Rosenblitt

notes that this poem is something of a reversal of "a

passage of desire from Walt Whitman's Song of Myself (11.199-201)."

(Modernism 157). She quotes these lines

from Whitman: "Twenty-eight young men bathe by the shore,

/ Twenty-eight young men and all so friendly; / Twenty-eight

years of womanly life and all so lonesome."

19. "when god lets my body be"

(CP2: 20)

According to Richard S. Kennedy, this poem was composed

for Dean Briggs' class in English Versification in

the spring of 1916 (Dreams 92). Along with "little tree" (CP 29),

"the bigness of cannon"

(CP 55), "Buffalo

Bill 's" (CP 90), "when life is quite through

with" (CP 11), and two others, "when god lets my body be"

was among Cummings' first published poems in The

Dial [68 (Jan. 1920): 24].

20-26. "Puella Mea" ["Harun Omar and Master

Hafiz"] (CP2: 21-28)

The longest poem that

Cummings ever published was written in praise of Elaine

Orr Thayer in the summer and early fall of 1919 while Elaine

was pregnant with Cummings' daughter Nancy. It is thus a kind

of companion-piece to "Epithalamion" (CP

3-7), commissioned in 1916 to celebrate the marriage of Elaine

and Scofield Thayer. Richard S. Kennnedy

writes that by publishing "Puella

Mea" in The Dial in January 1921 (48-54),

Thayer seemed to be making "a public declaration" that

Elaine and Estlin were a couple. "Shortly after," Kennedy

relates, Thayer and Elaine "reached an agreement for a French

divorce" (Dreams 215).

Harun Omar =

Omar

Khayyam (1048– 1131), Persian mathematician,

astronomer, and poet.

Master Hafiz

= Khwāja Shams-ud-Dīn Muhammad Hāfez-e Shīrāzī

(1315-1390), Persian poet known by his pen name Hafez

("the memorizer; the [safe] keeper") and as "Hafiz."

27. "in Just-" (CP2: 29)

goat-footed refers

to Pan, Greek woodland deity. In

a blog post at Harry Ransom Center, Jennifer [Alison]

Rosenblitt comments on "The goat-footed paganism

of E. E. Cummings." For more commentary on

this poem, see "On

'in Just-' " at the MAPS legacy site. See

also Iain Landles' deconstructive take

on the poem in "An

Analysis of Two Poems by E. E.Cummings"

[Spring 10 (2001): 31-43]. For responses

to Landles, see R. A. Buck, "When

Syntax Leads a Rondo with a Paintbrush:

The Aesthetics of E. E. Cummings' 'in Just-' Revisited."

[Spring 18 (2011): 134-159] and Etienne

Terblanche, "Oscillating Center

and Frame in E. E. Cummings's 'in Just-." [The Explicator

73.2 (2015): 105-108] For a consideration of the poem's

paganism and its place in the five-poem sequence "Chansons

Innocentes," see J. Alison Rosenblitt's E. E. Cummings'

Modernism and the Classics (77-89).

Richard

S. Kennedy reprints the first version of the poem

(with capitals begining each line and standard spacing

of the free-verse lines) in Dreams in the Mirror

(97). He reproduces a photo of the typescript in E.

E. Cummings Revisited (27). This first version of the poem,

which was composed for Dean Briggs' class in English

Versification in the spring of 1916, started out like this:

In just-Spring

When

the world is mud-luscious

The queer

old balloon-man

Whistles

far and wee,

And Bill

and Eddy come pranking

From

marbles and from piracies,

And it's

Springtime.

(qtd. in Kennedy,

Dreams 97)

In the

summer and fall of 1916, while living at his parents'

house at 104

Irving Street, Cummings began to restructure

his free verse poems by eliminating punctuation, using

capital letters mostly for emphasis, and creating radical

line breaks and non-standard spacings. To see a photo of

Cummings' first restructured draft of the poem, go to the

Tulips

& Chimneys page at the Cummings Archive.

For a discussion of Cummings' revisions of "in Just-",

see Michael Webster's overview of the poet's work in A

Companion to Modernist Poetry, "E. E. Cummings" (494-496).

Compare the rather tame free verse of the excerpt above with

the revised version of "in Just-"

published in The Dial [68 (May 1920): 580].

28. "hist whist" (CP2:

30)

Links:

29. "little tree" (CP2: 31)

Links:

31. "Tumbling-hair" (CP2: 33)

This poem was first published in Eight Harvard Poets

(1917) under the title "Epitaph" (10).

Richard S. Kennedy notes that the poem is "about innocence

betrayed or the vulnerability of beautiful

things, but it is expressed by means of a classical

subject, the abduction of Persephone by Hades, and treated

with the new technique he had developed . . . . It is an

image in action, presented with elliptical brevity" (Dreams

108). Charles Norman notes the likely allusion to Milton's

lines in Paradise Lost: "Not that fair field

/ Of Enna, where Proserpin gathering flowers, / Herself a

fairer flower, by gloomy Dis / Was gathered" (IV. 268-71; Norman,

Magic-Maker 39-40). See also the discussion of

the poem in J. Alison Rosenblitt's E. E. Cummings' Modernism

and the Classics (83-85).

32. "i spoke to thee" [Orientale I] (CP2:

34)

First published

as "Out of the Bengali" in The Harvard Monthly

59.3 (December 1914): 85.

41. "your little voice"

This poem was first published as "The Lover Speaks" in late 1917 in Eight Harvard Poets

(9).

53. "Humanity i love you" (CP2: 58)

It is instructive to consider why Cummings

placed this poem first in a section

called "La Guerre," poems about World War

I. The following passage from i: six nonlectures

seems relevant to

the context of the poem:

Whereas—by the very act of becoming its improbably gigantic self—New

York had reduced mankind to a tribe of pygmies,

Paris (in each shape and gesture

and avenue of her being) was continuously

expressing the humanness of humanity. Everywhere

I sensed a miraculous presence, not of

mere children and women and men, but of living human

beings; and the fact that I could scarcely

understand their language seemed irrelevant, since

the truth of our momentarily mutual aliveness created

an imperishable communion. While (at the hating

touch of some madness called La Guerre) a once

rising and striving world toppled into withering hideously

smithereens, love rose in my heart like a sun and beauty

blossomed in my life like a star. Now, finally and first,

I was myself: a temporal citizen of eternity; one with

all human beings born and unborn. (53)

the old howard = The Old

Howard Theatre,

on Howard St. in Scollay Square, Boston.

Long since demolished by "illustrious

punks of Progress" (CP 438), Scollay Square

and the Old Howard were for years "famous for

supplementing the curricula of Harvard students.

'Always Something Doing, One to Eleven, at the

Old Howard' read its ads in the Boston Globe, followed

by the titillating phrase, '25 Beautiful Girls 25' "

(Park).

Links:

54. "earth like a tipsy" (CP2:

59)

once

the discobolus of / one // Myron

= most likely a plaster cast of one of the

surviving bronze copies of Myron's

famous statue of a discus thrower.

Alison

Rosenblitt suggests that the poem "depicts

a drunken earth lurching around,

breaking the artefacts of human civilization.

This seems like earth under cannon bombardment"

("a twilight" 249). She further notes that

both crucifix and discobolus are "two beautiful

naked or nearly naked male bodies, smashed up

by the drunk cleaning woman who is earth. These are

not simply bodies, but specifically male bodies

created through art. . . . Earth destroys, equally, a

pinnacle of ancient art and an image which lies at the heart

of Christian art" (252).

56. "little ladies

more" (CP2: 61-62)

Even though all of its suggestive language

is in French, this poem was not able

to be published in the original 1923 Tulips and Chimneys.

It first appeared in & [AND] (1925) and was later

reprinted as poem TWO IX

in the book is 5

(1926).

Mimi à / la

voix fragile / qui chatouille Des / Italiens

= "Mimi with the fragile

voice who tickles Des Italiens." EEC remembers

two prostitutes, Mimi and (a few lines down)

Marie Louise Lallemand, whom he and Slater

Brown picked up in May, 1917 while waiting in Paris

to be posted to their ambulance section (see

Kennedy, Dreams 138-144).

Des Italiens

= the Boulevard Des Italiens, on the two

women’s regular beat "between the place de la République

and the place de la Opéra"

(Kennedy, Dreams

141). putain =

prostitute.

n'est-ce pas que

je suis belle / chéri? les anglais

m'aiment / tous,les américains

/ aussi. . . . "bon dos,bon cul de

Paris" = aren’t I beautiful, dear?

the English love me all of them, the

Americans too. . . . "good back, nice Parisian

ass"

Vierge / Priez /

Pour / Nous) = Virgin Pray For

Us.

se promènent

/ doucement le soir = walking slowly in the

evening.

les anglais / sont

gentils et les américains / aussi,ils

payent bien les américains

= the English are nice and the Americans

too, they pay well the Americans.

voulez- / vous couchez

avec / moi? Non? pourquoi?

= do you want to sleep with me? No? why?

la / guerre j'm'appelle

/ Manon,cinq rue Henri Monnier / voulez-vous

couchez avec moi?

= the war I’m Manon, 5 rue Henri Monnier do you

want to sleep with me?

te ferai Mimi / te

ferai Minette = I will let you

do Mimi I will let you do Minette.

[Both Mimi and Minette are pet names for a

cat--i.e., “pussy.”]

si vous voulez / chatouiller

/ mon lézard

= if you’d like to tickle my crack.

j'm'en fous des nègres

= I'm crazy about

black guys.

une boîte à

joujoux = a box of toys.

[Also jouir = to

play.]

toutes les petites

femmes exactes / qui dansent

toujours = all the little exact

ladies who dance always.

dis-donc,Paris //

ta gorge mystérieuse

/ pourquoi se promène-t-elle,pourquoi

/ éclat ta voix / fragile couleur

de pivoine? = tell me Paris, your

mysterious throat why does she walk you, why

does your fragile peony-colored voice burst?

63. "stinging" (CP 2: 68)

In "Modernist

Poetry and the Plain Reader's Rights," Laura

Riding and Robert Graves are probably correct in noticing an

allusion to Rémy de Gourmont's Litanies de la rose

(36) in the lines "silver // chants the litanies the

/ great bells are ringing with rose." In The Enormous Room,

Cummings quotes from Gourmont's poems "Le Verger"

(57) and "Chanson de l'automne" (219). (See Thierry Gillyboeuf

's "About Two French

Verses in The Enormous Room.") In addition,

Cummings could have read extensive quotations from Litanies

de la rose in Amy Lowell's volume Six French Poets

(1916). Riding and Graves seem put off by the "technical

oddities" of "stinging"--the lack of capital letters and

"spacing [which] does not suggest any verse form" (36).

For them, the poem is so fragmentary and "sketchy" that it

"might be made to mean anything" (36). They posit that any "precise

meaning" that the poem may have had was "lost . . . while writing

[it]." So they set out "to discover the original poem that was in

the back of the poet's mind" (36), and do so by concocting a 15-line

poem that begins: "White foam and vesper wind embrace. / The salt

air stings my dazzled face" (37). They conclude, however, that their

rhymed and conventionally-spaced version is "banal" because it

introduces too "many superfluous words and images" (38). Writing

this supposedly more formal version of the poem causes them to

laud the "carefully devised dreaminess" (39) of Cummings' poem, admitting

that it is "intensely formal," although they are uncertain whether

the "plain reader" is capable of applying the "critical effort" necessary

to appreciate "stinging" as a poem (40).

Richard

S. Kennedy reproduces a draft of the poem in his biography

Dreams in the Mirror, while reminding us

that "stinging" is only one of a large group of poems in

conventional free verse on a list that Cummings compiled

in the summer of 1916 under the heading "D.S.N." (Dreams

97). (What the initials "D.S.N." might signify is unknown,

but my guess is that they probably stand for "Do Something

New.") Unlike Riding and Graves's alternate poem, the first

version of "stinging" is written in the standard free verse

format of 1916--without radical line breaks and with regular

punctuation and initial capitals.

Stinging gold

Swarms

upon the spires,

Silver

chants the litanies,

The great

bells are ringing with rose—

The lewd

fat bells.

And a tall

wind

Is dragging

the sea for a dream,

For soon

shall the formidable eyes

Of the

world be

Entered

With sleep.

(qtd. in Kennedy, Dreams 98)

For the

final version, Cummings cut the last four lines of

the draft while making two crucial lexical alterations,

substituting "with // dream // -S" for "for a dream."

Cummings deletes all punctuation, along with the capital

letters at the beginning of the lines, while radically rearranging

the spacing of the words in lines 1-7 of the draft. To cite

one example, the words "wind / Is dragging the sea for a

dream" (lines 6-7) are lengthened into seven lines, five consisting

of only one word and the last line with only the hook-and-wave-pattern

of a hyphen and capital S. The sky-wind becomes taller and

visually ripples the dream-waves.

67. "the hours rise up putting off stars

and it is" (CP2: 72-73)

Richard

S. Kennedy notes that Cummings wrote the first version

of this poem "in November 1914, his senior year at

Harvard" (Dreams 122). Kennedy reprints the

first version, which is in long free-verse lines reminiscent

of Walt Whitman. The poem may also have been influenced

by Carl Sandburg's "Chicago," which first

appeared in Poetry Magazine in March 1914. When

he revised the poem in 1916, Cummings cut out some "sentimentalizing"

and "social posturing" and added the lines in the middle

about "a frail / man / dreaming / dreams / dreams in

the mirror" (Dreams 123). Kennedy notes that by

isolating the words "dawn," "wakes," "the world," "man,"

"dreaming," and "dreams" in lines of their own, Cummings emphasizes

the "main theme" of the poem: his notion of "dream" as a "vision

of some ultimate reality which is beclouded by the world"

(Dreams 124).

68. "i will wade out" (CP2: 74)

This

poem was first published in late 1917 as "Crepuscule" [French for

"Twilight"] in Eight Harvard Poets

(7). The compositor of the volume made a number

of errors in setting the type for this poem, creating non-existent

line breaks at "burn- / ing flowers" and "my / body."

In addition, as Richard S. Kennedy notes, the typescript

of the poem featured for the first time Cummings' lower-case

"i"--but "this little startler was never published, for the

copy editor apparently took it as a typing error and corrected

it" (Dreams 109).

71. "as usual i

did not find him in the cafés"

(CP2: 77)

This poem "was originally entitled 'Arthur

Wilson' after Cummings' roommate

in New York in 1917" (Kidder 39). The first

part of the poem depicts Cummings

searching for Wilson at rush hour; the second

part depicts their apartment, with its

crimson (the Harvard color) quilt and EEC's "geometrical"

paintings. (See Kennedy, Dreams 82,

139; Letters 13-14.) For more on Wilson, see

https://winslowwilson.com/.

The syntax of the

first sentence might be clarified by

a comma after "peregrinations" and a parenthesis

around "by inevitable tiredness

of flanging shop-girls." Perhaps also the

nouns and verbs are arranged in German fashion,

so that it is "the street" that "furnished"

and the twilight that "impersonally affords."

flanging = "to furnish with a flange, a protruding rim, edge, rib,

or collar."

woolworthian pinnacle = the

Woolworth

building, tallest before

1931. (See also 111. "at the ferocious

phenomenon of 5 o'clock" [CP1 201].)

73. [V] "Babylon slim"

(CP2: 79)

"Pretty / Baby" =

song written by Tony Jackson, Egbert Van Alstyne (music)

and Gus Kahn (lyrics), published in 1916. The

lyrics

of the song push the baby

metaphor too far, as one can see by

the chorus:

Everybody loves a baby that's why I'm in love

with you,

Pretty baby, pretty baby,

And I'd like to be your sister, brother,

dad and mother too,

Pretty baby, pretty baby.

Won't you come and let me rock you in

my cradle of love

And we'll cuddle all the time.

Oh, I want a lovin' baby, and it might

as well be you,

Pretty baby of mine,

Pretty baby of mine.

84. "one April dusk the"

(CP 2: 91)

Ο ΠΑΡΘΕΝΩΝ

= "O PARTHENON" or "The Parthenon," the name of the restaurant.

Under the pseudonym "Dorian

Abbott," Cummings' friend and mentor S. Foster Damon

(1893-1971) wrote in "Thirty Years of Harvard Aesthetes" that

in "the years 1914-16 . . . nearly thirty [Harvard] students, all

poets, painters, or something similar, . . . banded together informally

to enjoy life. They steeped themselves in Debussy, Huysmans, Stravinsky,

in Baudelaire, Beardsley, and Botticelli, and occasionally, it

must be confessed, in Wilde and Louys. They wandered through the

city in the evening seeking strange foods at unknown restaurants

of all nationalities. The most celebrated of these was the 'Parthenon'

on Kneeland Street, where, over the pilaf, the yiaorti [yogurt],

or the paklova [baklava], they argued anything from Rabelais

to Ravel" (39). The Parthenon restaurant is also depicted in

"when i am in Boston,i do not speak" (CP 116) and "The awful darkness of the town" (CP 933) [Etcetera

33].

89. "spring omnipotent goddess thou dost"

(CP 2: 97)

ragging the world --Robert Wegner

writes, "I interpreted the words 'ragging

the world' as meaning clothing the world,

that is, urging the grass to grow, inducing

leaves to emerge, buds to bloom. Cummings had

no objection to this ancillary reading, but explicitly

he wanted me to know that 'ragging, when

I wrote the poem meant turning to ragtime(music;)syncopating'"

("Visit" 68). See also EEC's poem "ta / ppin

/ g" (CP 78).

90. "Buffalo Bill 's" (CP 2: 98)

Buffalo

Bill = William F. Cody (1846-1917). Buffalo

Bill's Wild West Show enthralled

audiences from 1883 to 1910. For criticism

of the poem, see Thomas Dilworth's "Cummings's

'Buffalo Bill 's'," Rushworth M. Kidder's " 'Buffalo Bill 's'—an Early Cummings Manuscript"

(Harvard Library Bulletin 24.4, Oct. 1976), and Etienne

Terblanche's "Is There a Hero in this Poem? E.

E. Cummings's 'Buffalo Bill 's / defunct'."

Links:

96. "conversation

with my friend is particularly"

(CP 2: 104)

Rushworth Kidder suggests that the friend

is Scofield Thayer, editor of the Dial

(39). For Thayer's views on Cummings' poetry,

see James Dempsey's The Tortured Life of Scofield

Thayer (65-67).

98. "the waddling"

(CP 2: 106-107)

bloo-moo-n = a blue

moon, cocktail containing Tanqueray

Malacca gin, Curacao liqueur, sweet and

sour mix, and pineapple juice, shaken with

ice.

sirkusrickey

= a circus rickey, cocktail containing

gin, lime juice, grenadine and club

soda, over ice.

platzburg = though "Plattsburgh"

is a town on Lake Champlain in upper

state New York, Cummings probably

refers to an alcoholic beverage.

hoppytoad

= a hop toad, cocktail containing rum, apricot

brandy, and lime juice.

106. "riverly is a

flower" (CP 2: 115)

This poem apparently takes place in a

graveyard, perhaps a "post-impression"

of the same [?] experience briefly alluded

to in EIMI: "And after

Buffalo Bill(a graveyard 'New York' &)what fireflies

among such gravestones" (430/411).

108. "into the strenuous briefness"

(CP 2: 117)

In a May 1920 letter

to his father, Cummings states that "into the strenuous briefness" is his

favorite among a group of five poems recently published

in The Dial [68 (May 1920): 577]. (See Selected Letters, page

71. The note by Dupee and Stade is in error.) He writes: "This

poem is later in compositon than the other 4,and to my mind

more perfectly organised. I am confident that its technique

approaches uniqueness. After all, sans blague and Howells,it

is a supreme pleasure to have done something FIRST -- and "roses &

hello" also the comma after "and" ("and,ashes")are Firsts" (Letters 71).

The phrase sans blague

and Howells means something like "no joke and

[no William Dean] Howells." In his 1916 term paper "The Poetry

of a New Era," written in his final semester at Harvard, Cummings

quotes from a September 1915 column that William

Dean Howells wrote on the New Poetry: "The best things

in the new poets are of the oldest form, and where some of

the second-best brave it in the fashions which are supposed new,

after all it is only a reversion to the novelties of an earlier

day” (634). Despite what Howells may say, Cummings asserts

that he has done something "FIRST."

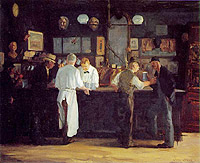

110. "i was sitting

in mcsorley's. outside it

was New York and beautifully snowing." (CP

2: 120-121).

McSorley's is an ale-house at 15 East

7th Street in the East Village, founded

in 1854 and still in business. The bar

used to be for men only—women were first

admitted in 1971.

Links:

|

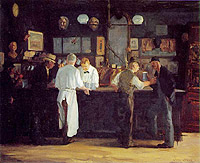

John Sloan, McSorley's

Bar

(1912, Detroit

Institute of Arts)

|

|

111. "at the ferocious

phenomenon of

5 o'clock" (CP 2: 122-123)

EEC goes to the

top of the Woolworth

building

to view rush hour. Milton Cohen writes

that "the poem's genius is . . . to find motion

in matter, describe matter in motion. Thus, for

all its towering verticality and perpendicular solidity,

the Woolworth Building is a 'swooping,' 'squirming'

'kinesis'." While Cohen agrees at least partially with

Richard S. Kennedy that "Cubism is the poem's rightful

source" [see Dreams 181-182], he also notes

that its "images (and the speaker with them) swoop,

rise, and squirm, they surge with a dynamism closer

to [John] Marin's vibrant Woolworth

Building watercolors

than to Picasso's static

Houses at Horta" (PoetandPainter

177). John Marin wrote of his Woolworth

Building series:

I see great forces at work; great movements; the large buildings

and the small buildings, the warring of the great and small.… Feelings are

aroused which give me the desire to express the reaction of these “pull forces”

.… while these powers are at work pushing, pulling, sideways, downward, upward,

I can hear the sound of their strife and there is great music being played.

For a particulary "swooping" wartercolor in Marin's series, see Woolworth Building #32. See also "as usual

i did not find him in the cafés"

(CP 71).

At left: Woolworth Building,

1913. Gelatin silver photograph.

New-York Historical Society

Links:

|

115. "the Cambridge ladies who

live in furnished souls" (CP 2: 127)

Longfellow = Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882), popular American poet,

author of inspirational poems like "A Psalm of

Life" and patriotic poems like "Paul Revere's

Ride."

Link:

Text of "the Cambridge ladies who live

in furnished souls" (Poetry Foundation)

116.

"when i am in Boston,i do not

speak" (CP 2: 128)

When / In Doubt Buy Of = an electric

sign, the rest of whose message

is obscured by rooftops.

Kneeland = street in downtown Boston

where the Parthenon restaurant was located. See the note

to "one April dusk the" (CP 84). See also

"The awful darkness of the town" (CP 933) [Etcetera

33].

hellas = Greece;

paklavaah meeah = one baklava,

a pastry described as "indigestible

honeycake" in line eight.

ΜΕΓΆ

ΈΛΛΗΝΙΚΟΝ

ΞΕΝΟΔΟΧΕΙΟΝ ΎΠΝΟΥ = "MÉGA HELLENIKÓN

XENODOCHEÍON HUPNOU" = "Grand

Hellenic Hotel for Sleeping." No doubt a ("cindercoloured

little") black and white tourist

photo on the wall of the restaurant.

118. "ladies and gentlemen

this little girl" (CP 2: 130)

the Frolic or the Century whirl--These

seem to be dances, but The Frolic

was also the name of a dance pavilion at Revere Beach

north of Boston.

119. "by god i want above

fourteenth" (CP 2: 131)

the singer = the Singer

Building,

finished in 1908, demolished in 1967. For

approximately one year, it was the tallest

building in the world.

121. "a fragrant sag of fruit

distinctly grouped" (CP 2: 133)

swims to Strunsky's = "Strunksy

Restaurants: 19 W. 8th Street (from 1917)

three restaurants in one. On the first

floor was Washington Square Restaurant, on the

lower floor was Washington Square Cafeteria

and Greenwich Village Cafeteria. (Also known as 'Three

Steps Down')."

124.

"when thou hast taken thy last applause,and when"

(CP 2: 136)

This poem was titled "A Chorus Girl" when it was first

published in late 1917 in Eight Harvard Poets

(4). This poem made an impression on some contemporaries.

In his memoir Exile's Return (1934, 1951), Malcolm Cowley

emphasizes the literary decadence of the "Harvard Aesthetes

of 1916" by quoting (without attribution) the last phrase in the

sonnet:

They had crucifixes in their bedrooms, and ticket stubs from

last Saturday's burlesque show at the Old Howard. They wrote, too, dozens

of them were prematurely decayed poets, each with his invocation to Antinoüs,

his mournful descriptions of Venetian lagoons, his sonnets

to a chorus girl in which he addressed her as “little painted

poem of God.” In spite of these beginnings, a few of them became

good writers. (35)

In addition, the short reader's report

that the poet and writer Clement Wood prepared for the publisher

of Eight Harvard Poets terms the last line of the sonnet

"quite effective." And in his review of Tulips and Chimneys,

Robert L. Wolf, a classmate of Cummings at Harvard, quotes this

sonnet entire, calling it "one of the finest poems in the book" (18).

125. "god pity me whom(god

distinctly has)" (CP 2:

137)

fattish drone / of I Want a Doll

= popular song from 1918 by composer

Harry Von Tilzer (1872-1946), and lyricists

Eddie Moran (b. 1871) and Vincent Bryan (1883-1937).

The song's

lyrics begin: "When I was just

a little kid I had a million toys

/ But when I saw a doll I just went wild." The

chorus begins: "I want a doll, I want a baby

doll to play with me."

139. "Thou in whose swordgreat story shine the deeds"

(CP 2: 151)

This poem was first published

in late 1917 in Eight Harvard Poets

(3).

Froissart

= Jean Froissart (1338-1410?), French

historian, author of The Chronicles

(1369-1410).

144. "this is the garden:colours come and go"

(CP 2: 156)

In her memoir, Hildegarde Watson reports

that in the summer of 1915, Cummings and her husband

"motored to Rochester [N.Y.] to the Watson house, where

Estlin wrote the now famous sonnet. . . . Mrs. Watson

placed it in her guest book where, later, I came across

it. It is arranged—and punctuated—differently from

the published version; there is no 'u' in 'color,' and

there are capitals at the beginning of each line!" (87).

Here is the first stanza of this sonnet as transcribed

by Hildegarde Watson:

This is the garden. Colors come and go:

Frail azures fluttering from night’s outer

wing,

Strong silent greens serenely lingering,

Absolute lights like baths of golden snow.

The poem appears with the same

punctuation and capitalization in Eight Harvard Poets

(1917). When the sonnet was published in Tulips

and Chimneys (1923), Cummings removed most

capital letters, retaining only those in words that

begin sentences, along with the two crucial capitals

in the words "Death's" and "They." He also made two simple

changes in punctuation in the first line--substituting

a colon for the period after "garden" and a comma for the

colon after "go"--adding more momentum to a line that nevertheless

still lingers slightly.

146. "it may not always be so;and i say" (CP

2: 158)

This poem was first published in Eight Harvard Poets

(6).

160. [SONNETS--ACTUALITIES VII] "yours

is the music for

no instrument" (CP 2: 172)

rathe = "quick in action, eager,

vehement" or "early" (Heusser, I

Am 175).

la bocca mia = "my mouth" [Italian].

Richard S. Kennedy points out that

this passage alludes to Dante, Inferno

V.136: "Francesca has told Dante that

her love for Paolo began when they were reading

the story of Launcelot and Guinivere together

and suddenly 'la bocca mi bacio tutto tremonte' ([he],

trembling all over, kissed my mouth)" (Dreams

237-238). According to Kennedy, like Paolo

and Francesca, "the poet and his lady risk all eternity

for love" (238). But Heusser sees death as the

overwhelming threat in the poem.

169. "I have found what you are like" (CP

2: 181)

Link: William McClelland, William Appling Singers &

Orchestra, Five Sonnets for Men's Voices: i have found what you are like [Albany Records]

170. "—GON splashes-sink" (CP 2: 182)

Three letters (G, O, and N) from a large

illuminated sign flash on the sink.

What are the other letters of the sign? Could

it be CALGON?

j'en doute,) chérie

= "I doubt it, dear" [French].

Back to the list of books

& [AND]

(1925)

The 1994 Complete

Poems publishes as

& [AND] only those new poems that

Cummings added to the poems left over from

the original 1922 Tulips

& Chimneys manuscript. Privately

printed to avoid censorship, this group of poems

Cummings titled & [AND], in honor of "the ampersand which

Seltzer

had denied him in Tulips and Chimneys"

(Kennedy, Dreams 252-253).

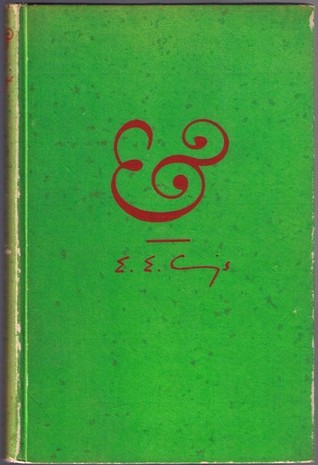

[See the headnote to Tulips & Chimneys

above.] At right: cover of first edition

of & [AND]. (Note

capital letters in Cummings'

signature.)

184. "I remark this beach has been used too.

much Too. originally"

(CP 2: 196)

flatchatte ringarom a .s

= "flat chattering aromas."

c'est // l'heure // exquise

= "it is the exquisite hour" [French].

Isabelle Alfandary notes that this phrase

is the last line of poem 6 ("La lune blanche")

in Paul Verlaine's collection La Bonne

chanson (1870).

i remind Me of Her —Alfandary

also notes that the English phrase

is a literal translation of "je me la souviens,"

a common French phrase that is not found

in Verlaine's poem. A more idiomatic translation

would be: "I remember her." (See Alfandary,

E. E. Cummings 63-64.)

189. "suppose / Life is an old man" (CP

2: 201)

Life speaks French, of course:

les / roses les

bluets = "roses, bachelor's

buttons"; Les belles bottes =

"pretty bunches"; pas chères

= "not expensive."

192. "here is little Effie's

head" (CP 2: 204-205)

In Spring 7, Alys Yablon notes

that "Effie's name may perhaps be

a play on the word 'ephermeral'" (51).

The six subjunctive crumbs may be derived

from Gilbert and Sullivan's anti-feminist

operetta Princess

Ida.

In the operetta, the princess of the title founds

a college for women and vows that students

and faculty will shut themselves off from

all contact with men. Lady

Blanche, the "Professor of Abstract

Science" at the college, expresses

her ambition to overthrow Princess

Ida in the following way:

|

|

Oh, weak Might Be!

Oh, May, Might, Could,

Would, Should!

How powerless ye

For evil or for good!

In every sense

Your moods I cheerless

call,

Whate'er your tense

Ye are Imperfect,

all!

Ye have deceived the trust I've shown

In ye!

Away! The Mighty Must alone

Shall be!

(264-265)

At the conclusion of the play, when Princess

Ida asks Lady Blanche whether she would

take her place should she resign, Blanche

responds:

To answer this, it's meet that we consult

The great Potential Mysteries; I mean

The five Subjunctive Possibilities--

The May, the Might, the Would, the Could,

the Should.

Can you resign? The prince May claim

you; if

He Might, you Could--and if you Should,

I Would! (293-294)

For a discussion of Princess Ida

in the context of its source (Tennyson's

The Princess)

and of attitudes towards

women in the late 19th and early 20th

centuries, see volume one of Sandra Gilbert

and Susan Gubar's No Man's Land: The

War of the Words, pp. 3-23. For another possible

Cummings borrowing from Gilbert and Sullivan,

see "mr u will not be missed"

(CP 551).

195. "i will be"

(CP 2: 207-208)

dea d tunes

OR s-crap

p-y lea Ves flut te rin g should read "dea d tunes

OR s-cra p-y lea Ves flut te rin g"--

EEC is writing "scrapy" not "scrappy."

199. "gee i like to think of dead

. . ."

(CP 2: 212-213)

inti

= intimate [adjective].

201. "(one!) // the wisti-twisti barber"

(CP 2: 214)

See Louis C. Rus, "Cummings'

'(one!)'." Explicator 15 (Jan.

1956), item 40. Rus notes how the grammatical

ambiguities in the poem reinforce

its message of oneness.

203. "O It's Nice To Get Up In,the slipshod mucous

kiss" (CP 2: 217)

Richard S. Kennedy notes that the poem

quotes from a popular song sung by

Harry

Lauder in the British music halls:

Oh, it's nice to get up

in the morning

When the sun begins to shine,

At four or five or six o'clock

In the good old summer time.

But when the snow is snowing,

And it's murky overhead

Oh, it's nice to get up in the morning,

But it's nicer to lie in your bed!

Kennedy quotes a slightly different

version of the first stanza in Selected

Poems 73. Here's the complete performance

(with spoken interlude) of "It's Nice to

Get Up in the Morning But It's Nicer to

Lie in Bed."

207. "the bed is not very big" (CP 2: 221)

et tout en face = "and right in

front" [French];

poilu = "hairy, shaggy, furry" [French]. Milton Cohen suggests that

the gaslight clothes the crucifix on the wall "in a sensuous, nappy fur"

(Poet 131). But the word poilu was also a slang term for French

foot-soldiers in World War I.

208. "the poem her belly marched through me as"

(CP 2: 222)

a trick of syncopation Europe has

refers to James Reese Europe (1880-1919),

pioneer bandleader and jazz composer.

Gilbert

Seldes wrote in The Seven Lively Arts that Europe had "that interior

response to syncopation . . . to the highest

possible degree" (156). See

239. [ONE-XII] "(and i imagine"

216. "a blue woman with sticking out breasts hanging"

(CP 2: 230)

Bishop

Taylor = probably Mormon Bishop

Thomas Taylor (1826-1900). D. Michael Quinn

writes: "On 26 July 1886, his sixtieth birthday,

the Salt Lake stake high council 'suspended'

Thomas Taylor as bishop of the Salt Lake

City Fourteenth Ward. . . . Three teenagers testified

that while each was alone in bed with Bishop Taylor,

the bishop has used the young man's hand to masturbate

himself" (276-277). The polygamous Taylor further

testified at the church trial that he had not "practiced"

such acts since he was a teenager (presumably before

he was married). Quinn notes that "in his autobiography,

however, Taylor later described the charges as 'trumped

up slander' " (277).

Back to the list of books

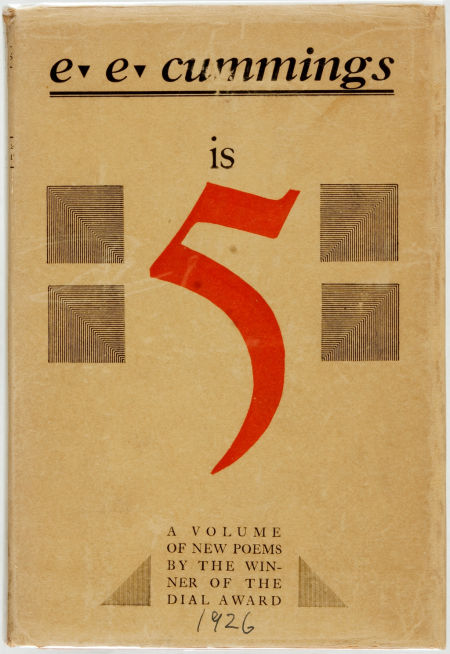

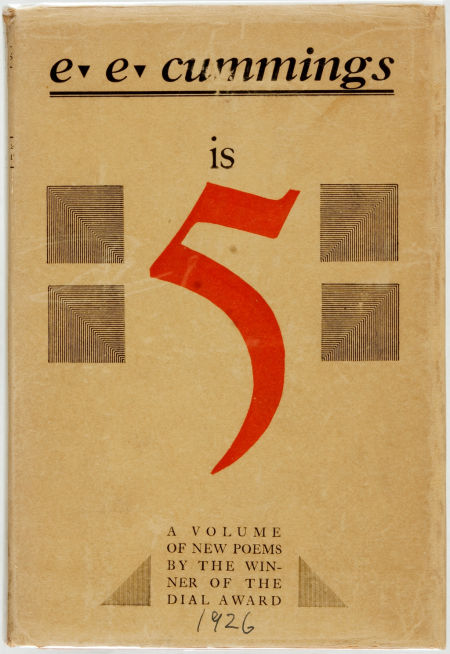

is 5 (1926)

On March 1, 1926, E. E. Cummings wrote

to tell his publisher that "after some

weeks' work" his book is 5 was "finally arranged.

. . including . . . poems from my last

book(AND)" (Firmage, "Afterword"). In the same

letter, Cummings assures Horace Liveright that

his personal typesetter Samuel Aiwaz Jacobs (1890–1971), would be in

charge of setting up the book, since he

understands my arrangement. . . which

involves

not merely complicated sequential

relationships between groups of poems

which constitute the whole,but definite

numerical relationships—the total

number of poems having its precise significance

just as the number of poems in each subdivision

has its precise significance. (quoted in Firmage,

"Afterword")

While Cummings' editor George Firmage

has remarked that the book seems to

be structured in patterns of 4 and 5, he offers

no further elucidation of this statement.

(However, see dust jacket at right.) To the new poems

in is 5, Cummings added ten previously published

poems from & [AND]--eight were from

the original 1922 Tulips & Chimneys

manuscript, and are printed there in the Complete Poems. Two of the

added poems are from the new poems printed

in & [AND] (1925).

The poems in is 5 are divided

into five sections, numbered straightforwardly

enough, ONE, TWO, THREE, FOUR, and FIVE. Since

they are already printed in their original

places in Tulips & Chimneys

and &

[AND], the ten added poems

are not reprinted in

the version of is 5

given in the Complete

Poems. Below is a chart

listing the numbers of poems in the Complete Poems edition

and the numbers in the 1926 edition

of the book. (The “+ 4” in each count indicates

that Cummings' poem number “ONE I” consists

of 5 sonnets, which Firmage counted as separate

poems.)

| As published in is 5 (1926) |

As printed

in Complete Poems

(1994) |

|

ONE

44 poems (40 + 4)

TWO

11 poems

THREE 10 poems

FOUR

18 poems

FIVE

5 poems

total:

84 + 4

|

ONE

38 poems (34 + 4)

TWO

10 poems

THREE

7 poems

FOUR 18 poems

FIVE

5 poems

total:

74 + 4

|

The following is a chart of the ten

poems added to is

5 (1926), with a corresponding

column detailing their placement

in the Complete

Poems (1994):

| Poems added to is 5 (1926) |

Complete Poems (1994) |

1.

ONE, VII "the waddling"

2. ONE, XVI "it started when Bill's chip

let on to"

3. ONE, XXI "i was sitting in mcsorley's."

4. ONE, XXIV "Dick Mid's large bluish

face without eyebrows"

5. ONE, XXXIII "Babylon slim"

6. ONE, XXXVI "ta" |

1. Tulips: "Portraits" XXVI

(CP 98)

2. Chimneys: Sonnets—Realities

XIII (CP127)

3. Tulips: Post Impressions VIII

(CP 110)

4. Chimneys: Sonnets—Realities

XX (CP 134)

5. Tulips: "Portraits" V (CP

73)

6. Tulips: "Portraits" IX

(CP 78)

|

| 1.

TWO, IX "little ladies more" |

1. Tulips: "La guerre" IV

(CP 56)

|

1.

THREE, IV "impossibly"

2. THREE, V "inthe,exquisite;"

3. THREE, VII "Paris;this April sunset

completely utters" |

1. & A: Portraits II (CP 191)

2. Tulips: "Portraits" XVIII

(CP 87)

3. & A: Post

Impressions III (CP 183)

|

|

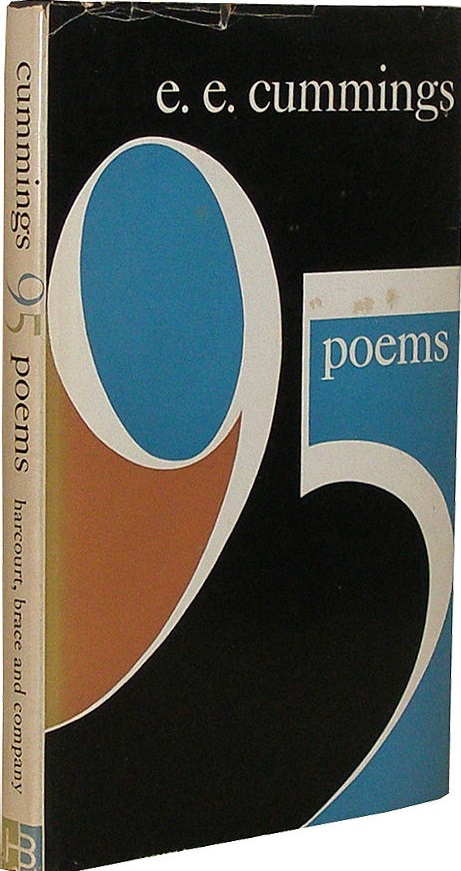

Dust jacket of is 5, designed by S. A. Jacobs

|

Cummings added two

satirical sonnets to section ONE, bringing

to four the number of sonnets between

the five each that begin and end the

volume. There was already one quasi-sonnet

in section ONE, "poets yeggs and thirsties,"

and in section TWO, the famous " 'next to of

course god america i" (CP 267). In the notes that

follow, the Roman numeral after each capitalized section

number corresponds to the numbers given in Complete Poems.

As the charts above indicate, because no

poems were added to sections FOUR and FIVE, these

sections retain the numbering of the original

volume.

225. [ONE I] III. GERT "joggle

I think will do it although the glad"

a Beau Brummell = a cocktail consisting

of 1 oz. bourbon, 1/2 oz. Prunella,

1 oz. orange juice, and 1/4 tsp. sugar.

"gimme a swell fite = give me

a swell fight.

Rektuz,Toysday nite = Rector's,

Thursday night. Rector's

= restaurant in the theatre

district frequented by the nouveau

riche.

where uh guy gets gayn troze uh lobstersalad

= where a guy gets gay and throws a

lobster salad.

228. [ONE II]

"Poem,Or Beauty Hurts Mr. Vinal"

(SP 152).

These notes are greatly indebted to Lewis H. Miller's "Advertising in Poetry: A Reading of E. E. Cummings'

'Poem, or Beauty Hurts Mr. Vinal'," Word & Image 2 (1986):

349-362. Cummings' poem was first published in December 1922, in the little

magazine S4N (Firmage, Bibliography

48). Cummings' title refers to a poem by Harold

Vinal (1891-1965) called "Earth

Lover," from his first book, White April (1922), published in

the Yale Younger Poets Series:

EARTH LOVER

Old loveliness has such a way with me,

That I am close to tears when petals

fall

And needs must hide my face against a

wall,

When autumn trees burn red with ecstasy.

For I am haunted by a hundred things

And more that I have seen on April days;

I have held stars above my head in praise,

I have worn beauty as two costly rings.

Alas, how short a state does beauty

keep,

Then let me clasp it wildly to my heart

And hurt myself until I am a part

Of all its rapture, then turn back to

sleep,

Remembering through all the dusty years

What sudden wonder brought me close to

tears.

—Harold Vinal

In the 1920's, Vinal was editor of Voices,

a long-lived poetry quarterly that was

"radically defunct" only in the sense that it did

not publish modernist poetry--at least not in 1922.

Cummings himself later published a poem in Voices:

“after screamgroa” (CP 656) [Voices 137 (Spring

1949): 18] (cf. Firmage 58). In 1945, when the Poetry

Society of America presented Cummings with its

Shelley Memorial Award, the prize was announced by

the Society's president, Mr. Harold Vinal (Kennedy, Dreams

405).

Boston

Garter: In pre-elastic

days, men used garters to keep

their socks up.

Lydia

E. Pinkham:

Manufacturer of cure-all remedy

for "women's" ailments. Her "Vegetable

Compound" was a mixture of roots, seeds, and 18% alcohol.

Just Add Hot Water And Serve

-- From a Campbell Soup ad.

merde = shit [French].

God's / In His andsoforth: "God's

in his heaven -- / All's right with

the world" (Robert Browning,

Pippa Passes).

Turn Your Shirttails Into Drawers:

Parody of ad for Imperial "Drop

Seat" Union Suit, long underwear with a buttoned

seat panel.

A- mer i ca,I love, You = "America,

I Love You" (1915), popular

song with words by Edgar Leslie and

music by Archie Gottler. As one can hear from

this recording of the song by Dan Levinson and His Canary

Cottage Dance Orchestra, Cummings'

punctuation and spacing of the words imitates

the tune and rhythm of the chorus:

"America, I love you! / You're like a sweetheart

of mine! / From ocean to ocean, / For you

my devotion, / Is touching each bound'ry line. / Just

like a little baby / Climbing its mother's knee, /

America, I love you! / And there's a hundred

million others like me!" In his essay on Gaston Lachaise

(1920) Cummings wrote of a critic who could "comfort

himself with the last line of that most popular

wartime song, America I Love You

which goes, 'And

there’re a hundred million others like

me' " (Miscellany 23). See also

" 'next to of course god america i" (CP

267) and "little joe gould has lost his

teeth and doesn't know where" (CP 410).

littleliverpill- / hearted:

Refers to ads for Carter's Little Liver Pills.

Nujolneeding- Nujol

was a widely advertised laxative.

There's-A-Reason:" Slogan for

Grape Nuts cereal and Instant

Postum, a coffee substitute

containing no caffeine.

Odor? / ono. Odo-ro-no

was a "toilet water" sold

to prevent "excessive perspiration."

comes out like a ribbon lies flat on

the brush: Slogan for Colgate's

Ribbon Dental Cream.

|

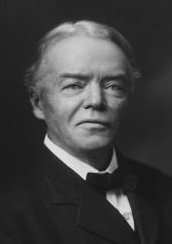

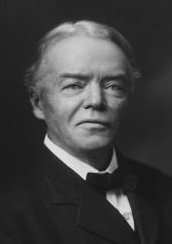

230. [ONE-III] "curtains part"

Kirkland Street in Cambridge,

Mass., just down the street from

Cummings' boyhood home at 104 Irving Street.

Professor Royce =

Josiah

Royce (1855–1916), Professor

of Philosophy at Harvard College

in Cummings' youth. In six nonlectures,

EEC writes, "I myself experienced astonishment

when first witnessing a spectacle which frequently

thereafter repeated itself at professor Royce's

gate. He came rolling peacefully forth,

attained the sidewalk, and was about to turn

right and wander up Irving, when Mrs Royce shot

out of the house with a piercing cry 'Josie! Josie!'

waving something stringlike in her dexter fist.

Mr Royce politely paused, allowing his spouse to catch

up with him; he then shut both his eyes, while she

snapped around his collar a narrow necktie possessing

a permanent bow; his eyes thereupon opened, he bowed,

she smiled, he advanced, she retired, and the scene

was over" (25). See also six nonlectures

29-30. Photo of Josiah Royce, with bow tie, at left. |

231. [ONE-IV] "workingman

with hand so hairy-sturdy" (CP 2: 245)

The poem was first published in Secession

2 (July 1922): 4.

but when will turn backward O backward Time in your no thy

flight : The speaker remembers the first two lines of "Rock

Me to Sleep" (1860) by Elizabeth

Akers Allen (1832–1911): “Backward, turn backward, O Time, in

your flight, / Make me a child again just for tonight!” The rest of

the first stanza longs for the presence of an absent mother: “Mother,

come back from the echoless shore, / Take me again to your heart as of

yore; / Kiss from my forehead the furrows of care, / Smooth the few silver

threads out of my hair; / Over my slumbers your loving watch keep;— / Rock

me to sleep, mother, – rock me to sleep!”

en amérique on ne

boit que de Jingyale = "in america

they only drink Ginger ale" [French]. Cummings

is probably remembering the final panel of a wartime Krazy Kat

cartoon (09/29/1918) in which Ignatz Mouse introduces

a temperance singer: "Brother Benjamin will now sing, "The

rouge on father's beezer he now gets from Jingy Ale." Both Herriman and Cummings

conflate the ginger ale of temperance (or prohibition) with the "Jingo ale"

of excessive patriotism. [See the note below on "Over There" and " 'next

to of course god america i" (CP 267).]

kaka = crazy, crappy.

over there, over there =

Part of refrain of George M. Cohan's

popular song "Over There,"

praising American troops going to fight "over

there" (in Europe) in World War I. Cummings'

reference turns on its head the

line from the song, "And we won't come back

'till it's over over there." For complete

score and lyrics, click on image at right. For

the complete lyrics and three audio versions of

the song, see the "Over There" page

at FirstWorldWar.com.

"Over There" on You Tube: (versions

sung by Nora Bayes

and Arthur

Fields).

over there, over there =

Part of refrain of George M. Cohan's

popular song "Over There,"

praising American troops going to fight "over

there" (in Europe) in World War I. Cummings'

reference turns on its head the

line from the song, "And we won't come back

'till it's over over there." For complete

score and lyrics, click on image at right. For

the complete lyrics and three audio versions of

the song, see the "Over There" page

at FirstWorldWar.com.

"Over There" on You Tube: (versions

sung by Nora Bayes

and Arthur

Fields).

all the glory that or which was Greece = garbling of E. A. Poe's

lines from "To Helen"--"Thy Naiad airs

have brought me home / To the glory that

was Greece, / And the grandeur that was Rome."

grandja / that was dada? Dadaism

was a nihilistic anti-art movement

begun in Zürich, Switzerland

during World War I. By 1926, when

Is 5 was published,

the dada movement was a spent force. For the possible

influence of the Dada movement on Cummings, see Tashjian,

Skyscraper Primitives (165-187), Ruiz,

"The Dadaist Prose of Williams

and Cummings," and Abella, " 'I am that I am': The Dadist Anti-Fiction

of E. E. Cummings." For doubts about Dada's influence

on EEC, consult Cohen, PoetandPainter

(48; 248) and Webster, Reading

Visual Poetry after

Futurism (115-134). For a view of The

Enormous Room as depicting an instinctive Dadaist attitude,

see Webster, "The Enormous

Room: A Dada of One’s Own." For a contemporary view of the

death of Dada and its aftermath, see Matthew Josephson, "After

and Beyond Dada." [Broom 2.4 (July 1922): 346-350].

See also Peter Nicholls' article, "Life Among the Surrealists:

Broom and Secession Revisited."

what's become of Maeterlinck

refers to the symbolist poet

and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck

(1862-1949), author of the plays Pelleas

and Melisande (1893) and The

Blue Bird (1905). In 1922, Maeterlinck published

a sequel to The Blue Bird called Les

Fiançailles, but in later life his

attention had turned increasingly away from

drama towards scientific and occult topics.

This line and the next also parody the first

lines of Robert Browning's "Home

Thoughts from Abroad": "Oh to be in England

/ Now that April's there." (See the note for "MEMORABILIA.")

ask the man who owns one = advertising

slogan for Packard

automobiles.

ask Dad,he knows = advertising

slogan for Sweet Caporal

cigarettes.

232. [ONE-V] "yonder deadfromtheneckup

graduate of a"

nascitur = the third person

singular present indicative of the

verb nascor, meaning that "he / she /

it is being born, arises, originates, begins,

is produced, springs forth, proceeds, grows,

is found" [Latin]. cf 262. "voices

to voices,lip to lip" and Him

III.vi (132 / 126).

233. [ONE-VI] "Jimmie’s got a goil"

234. [ONE-VII] "listen my children

and you"

listen my children and you / shall

hear = the first line of "The

Landlord's Tale. Paul Revere's Ride"

by Henry

Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882), popular American poet.

The contrast between the intrepid hero Paul Revere and Mr.

Do-nothing is evident.

(eheu / fu / -gaces Postu- / me boo //

who refers to Horace, Odes,

II.14:

Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume,

labuntur anni nec pietas moram

rugis et instanti senectae

adferet indomitaeque morti:

"Ah, Postumus, Postumus, how fleeting

/ the swift years--prayer cannot delay

/ the furrows of imminent old-age / nor hold

off unconquerable death."

235. [ONE-VII] "even if

all desires things moments be"

ou sont les neiges... part of

the refrain from the "Ballade des

dames du temps jadis" [Ballade of the Dead

Ladies] by François Villon (1431-1464?):

"Mais ou sont les neiges d'antan?"

[But where are the snows of yesteryear?].

Satter Nailyuh = Saturnalia,

Roman festival held at the winter solstice;

a time of license. The holiday season,

as seen by a denizen of New York during

prohibition. (Viz.: "in dem daze kid Christmas

/ meant sumpn".)

237. [ONE X] "nobody

loses all the time"

McCann He Was A Diver = Irish-American

song with the following lyrics, as recorded

by musicologist J. D. Robb (1892-1989).

The recording is part of the John Donald

Robb Archive at the University of New Mexico's

Center for Southwest Research.

McCann,

he was a diver, and he worked beneath

the sea,

Off a Jersey pier, off a Jersey pier.

O'Reilly worked the pump above, his hand

upon the line,

Pumping atmosphere, pumping atmosphere.

One day McCann was walking on the bottom

of the sea.

He met a mermaid and she said, "McCann,"

she said, said she:

"You look just like a devil-fish and

will you marry me?"

"Oh ho!" says McCann, says McCann, "Pull

me up O'Reilly where it's dry,

For I met a lady down below, and she

has a fishy eye.

Oh, she's looking nice and neat

But bedad she has no feet—

Pull me up O'Reilly where it's dry."

Of course, this movement up from the

sea bottom is the opposite of Uncle Sol's

mechanical movement down into the earth.

239.

[ONE-XII] "(and i imagine"

The poem was first published in Secession

2 (July 1922): 2.

As Norman Friedman notes in

Spring 3 (1994):

124-125, this poem depicts a nativity

scene.

angels with faces like Jim

Europe = James Reese Europe

(1880-1919), jazz bandleader and composer

who worked in Paris during World War I. Friedman

writes: "Alan Rich, in New York Magazine

for June 12, 1978, says James Europe was 'a promising

black composer who was murdered (by the drummer

in his band) in 1919' (81). . . James Lincoln

Collier, in The Making of Jazz (Delta,

1978), says, 'James Reese Europe, the kingpin of the

Clef Club,' was among 'the first American black musicians

of this period to reach Europe...as military bandsmen

accompanying the American Expeditionary Force in

the First World War" (314). Collier, readers of

this Journal may recall, is a nephew of William Slater

Brown, Cummings' companion in The Enormous

Room. The plot thickens! Marshall W. Stearns, in

The Story of Jazz (NAL Mentor, 1956, 1958),

praises Europe: 'The earlier minstrel-concert-vaudeville

orchestras of Wilbur Sweatman, Will Marion

Cook, and James Reese Europe (the favorite of

dancers Vernon and Irene Castle) were gradually supplanted

[and diluted] by Vincent Lopez, Ben Selvin, Earl Fuller

(with Ted Lewis), and Paul Whiteman, who supplied the

'new' jazz music, polished up for dancing....Lt.

James Reese Europe...might have been the Negro Paul

Whiteman if he had lived...' (113, 117). Leonard

Feather, in The Encyclopedia of

Jazz (Crown Bonanza Books, 1960), has an entry on

James Reese Europe: b. 1881, d. 1919, 'stabbed to death

in a night club altercation' " (211).

Friedman further notes

that the poem was first published "in

1922, in Secession (48).

This nevertheless also dates the poem after

Europe's death in 1919, which gives special poignancy

to the reference, if indeed Cummings wrote it

after Europe died. The effect remains, however,

of the transcendent presence of the angels, in

the midst of this coarse and mundane setting,

being imaged via the epiphany of Jim Europe."

For more information

on Jim Europe, click on the image

and links at right, and / or consult Reid

Badger's excellent A

Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese

Europe (New York: Oxford UP,

1995).

Additional

Links:

|

Jim Europe's

"Hellfighters" Band

(with RealAudio clips)

Songs

of James Europe

James Europe

Biography

Military

Music: Sousa and the Hellfighters

Europe

Gravesite

Order Jim Europe CD

from Inside Sounds /

Memphis Archives

PO Box 171282

Memphis, TN 38187

Phone: 800-713-2150

Memphisarc@AOL.com

|

243. [ONE-XVI] "why are

all these pipples taking their hets off?"

The first line imitates the diction

of Krazy

Kat, Cummings' favorite cartoon character.

See Taimi Olsen's article, " 'Krazies...of indescribable

beauty': George Herriman's 'Krazy Kat' and

E. E. Cummings."

the famous doctor who inserts / monkeyglands

= Serge Voronoff (1866-1951).

For all the interesting details, see Thierry

Gillyboeuf, "The Famous Doctor

Who Inserts Monkeyglands in Millionaires"

Spring 9 (2000): 44-45.

246. [ONE-XIX] "she being Brand"

Consult Fred Schroeder's "Obscenity

and Its Function in the Poetry of E.

E. Cummings," as well as Barry Marks, E. E.

Cummings (74-75), Karen Alkalay-Gut,

"Sex and the Single

Engine: E. E. Cummings' Experiment in

Metaphoric Equation" [Journal of Modern

Literature 20 (1996): 254-258], and especially

Lewis H. Miller. Jr.'s "Sex

on Wheels: A Reading of 'she being Brand

/ -new'," [Spring 6 (1997): 55-69].

thoroughly oiled the universal / joint --a necessary operation

with early motor-cars. For a discussion

and illustrations, see Miller 60-61.

slipped the / clutch --like flooding

the carburetor and "somehow"

getting into reverse, this is a beginner's mistake.

i touched the accelerator --Miller

writes that "the reference to the

accelerator is not to the foot pedal but to

the button-tipped hand throttle," which

beginners were advised to use "for the first few

days until the other details of driving had

been mastered" (62-63).

248. “oDE” [ONE-XXI]

toothless . . . bipeds

. . . hairless--EEC may be referring

here to a famous anecdote concerning the

philosopher Diogenes the Cynic (412-323 BC): "Plato

had defined Man as an animal, biped and featherless,

and was applauded. Diogenes plucked

a fowl and brought it into the lecture room

with the words 'Here is Plato's man' " (Laertius 138).

The chagrined Plato supposedly then added to

his definition, "having broad flat nails."

249. "on the Madam's best april the" [ONE-XXII]

The poem was first published in Secession

2 (July 1922): 1.

According to Robert Wegner, ["A Visit

with E. E. Cummings" Spring

5 (1996): 59-70] Cummings told him that

this poem's "words are spoken by an illiterate

Irish woman" (64). The woman is apparently

a "cook."

252. "than(by yon sunset’s wintry glow"

[ONE XXV]

by the fire's ruddy

glow / united--Cummings

may be referring to the sentimental Victorian

poem "Sitting

by the Fire" by Henry Kendall (1841-1882):

"Gleesome children were we not? /

Sitting by the fire, / Ruddy in its glow, / Sixty

summers back— / Sixty years ago."

it isn't raining

rain, you know = parody of the

refrain of the popular song "April

Showers" (1921), with music by Louis

Silvers and lyrics by B. G. DeSylva:

"Though April showers / May come your way, /

They bring the flowers / That bloom in May; / And

if it's raining, / Have no regrets; / Because,

it isn't raining rain, you know, / It's raining

violets." This song was one of Al Jolson's big

hits. Gilbert Seldes wrote in The Seven Lively Arts:

“I have heard him [Al Jolson]

sing also the absurd

song about "It isn't raining rain, It's raining violets" and remarked

him modulating that from sentimentality into a conscious

bathos, with his gloved fingers flittering together and his

voice rising to absurd fortissimi and the general air of kidding

the piece” (194-195).

254. "MEMORABILIA" [ONE-XXVII]

(CP 2: 270-271)

These notes are indebted to three items

in The Explicator, all entitled "Cummings'

MEMORABILIA": Clyde S. Kilby, 12 (1953),

item 15, Cynthia Barton, 22.4 (Dec. 1963), item

26, and H. Seth Finn, 29.5 (Jan. 1971), item 42. See

also Curtis Faville's blog entry: "Believe

You Me Crocodile—Eigner Cummings The

Typewriter & A Poem." The

title refers to Robert Browning's

poem "Memorabilia,"

which begins, "Ah, did you once see Shelley

plain?" This poem was written

after Cummings toured Venice with his parents

in late July, 1922 (Kennedy, Dreams 242).

stop look & / listen = slogan posted on railway platforms.

Venezia = Venice; Murano

= town near Venice where glass objects

d'art are made

nel / mezzo del cammin' = "midway

in the road [of our life]" --Dante,

Inferno I.1.

the Campanile = bell-tower

in the Piazza San Marco, Venice.

cocodrillo-- = "a large

stone crocodile which is part of a statue

of St. Theodore on a tall column overlooking

the Piazza San Marco" (Barton). Baedekers

= travel guides.

de l'Europe // Grand and Royal

= names of hotels in Venice.

their numbers / are like unto the

stars of heaven --After Abraham

showed his faith in the Lord by being willing

to sacrifice his only son Isaac, an angel promised

to multiply his "descendants as the stars

of heaven" (Genesis 22: 17). See also Genesis

15: 1-6.

Ruskin = John

Ruskin (1819-1900), author of The Stones of Venice (1851-53).

thos cook & son British

travel bureau with offices throughout

Europe: the company issued travelers'

checks and organized tours.

(O to be a metope / now that triglyph's

here) Parody of the first

lines of Robert Browning's "Home

Thoughts from Abroad": "Oh to

be in England / Now that April's there." H. Seth Finn

suggests that with this exclamation, the speaker

longs for "a meaningfulness in life which would

place him in the universe with the same comfortable precision

with which a metope fits between two triglyphs in the Doric

order."

Clyde Kilby writes that a metope and triglyph "are architectural terms

and describe a portion of a Doric frieze,

the metope being the decorated

section between the triglyphs." They are usually

placed horizontally in alternation on the

lintels of Greek buildings like the Parthenon.

(See this

photo of metopes and triglyphs on the Parthenon.)

The triglyph consists of three vertical lines

contained within the two horizontal lines

of the lintel. Lou Rus has suggested that the

metopes should be seen as the open "space for creating

a new art," which exactly corresponds with the

etymology of the word. The Greek metope means

"between or amidst the opae or tie-beams

(rafters)." Vitruvius explains when that ancient

carpenters "cut off the projecting ends of the

beams" the butt ends flush with the wall "had an ugly

look to them, [so] they fastened boards, shaped as

triglyphs are now made, on the ends of the beams, where

they had been cut off in front, and painted them with

blue wax" (107). Vitruvius says further: "The Greeks

call the seats of tie-beams and rafters όπαί [opae], while our people call

these cavities columbaria (dovecotes). Hence,

the space between the tie-beams, being the space

between two 'opae,' was named by them μετόπη [metope]" (108). "Seat" must

be where the beams cross another member, creating

an opening or space between the beams. The Greek

word ope, opai means just what it sounds

like, "open, openings." These empty spaces

were often filled with art--little bas-relief sculptures,

for example. So "to be a metope" could mean to be in

that space where new art is created, to be alive art

and not dead (and misunderstood) history. It could

also mean, simply, "to be art"--to be those little sculptures

rather than a rigid and decorative triglyph (three

stiff virgins?) at the end of a beam. The "marriageable

nymph[s]" do seem to approach art as decoration or fashion,

knick-knacks for their future homes in "Cincingondolanati":